By Samantha Sunne

As data collection, algorithms and social media become more and more influential in a reporter’s day-to-day life, journalists should grapple with a question: How can we incorporate data, and keep up with trends, while keeping diversity and inclusion in mind? How can we avoid leaving some groups behind, or emphasizing a status quo that leaves historically excluded communities at a disadvantage?

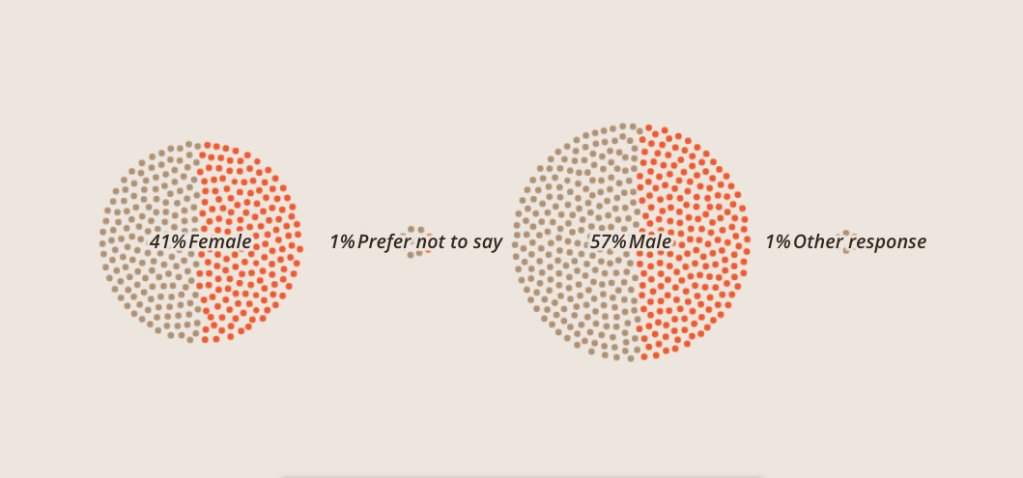

Diversity, equity and inclusion – sometimes abbreviated to DEI – has gotten more attention in the journalism community in recent years. Studies show that newsrooms in the US tend to be less diverse than the communities they represent and serve. Around the world, data journalists face similar issues, according to the 2017 News Nerd Survey by OpenNews.

So: How can we make our data journalism more diverse and inclusive, given these very real challenges? To start, Neema Roshania Patel, editor of The Washington Post’s Next Generation team, wrote a terrific set of five framing questions for a story for Poynter:

- Are we including the voices of the people most affected by what’s happening?

- How are we defining “experts” in this story?

- Are we engaging with a diverse range of sources, even when the story isn’t explicitly about marginalized groups?

- Are we making assumptions about our readers?

- How are we explaining our process to sources?

These framing questions touch on many aspects of ethical journalism, such as building trust with readers, quoting diverse sources and identifying your audience. You can find excellent resources for some of these challenges from groups such as Trusting News or the Solutions Journalism Network. This bonus chapter will focus on achieving these goals through data reporting, via current guidance, tools, and tips from journalists who are putting these efforts into practice.

Don’t get trapped in old patterns

In September 2022, the Kansas City Defender, a multimedia Black news source, published an alarming story: A local pastor warned that women were disappearing from a Black neighborhood in Kansas City. Other local outlets, like the Kansas City Star and KMBC-9, ignored the claim – until, that is, the Kansas City Police Department (KCPD) put out a statement calling the claim a baseless rumor.

Using law enforcement data, such as 911 dispatches and police officer reports, is very common in data journalism – so much so that it is often what people are referring to when they say “crime data.” In this case, KCPD data backed up the department’s statement: very few people had gone missing recently in the city, and homicides were rare.

But controversy erupted weeks later, when a man was arrested in a nearby town. He had kidnapped at least one woman – possibly many more –from the very area the Defender had alleged.

By that point, outlets, including the Star and KCTV-5, had run stories like, “‘Completely Unfounded’: Rumor about serial killer in Kansas City is untrue, police say.” These stories relied mainly on police sources – both human and data – for their facts.

This occurrence is a perfect example of how official data can sometimes be misleading, instead of enlightening – and how this is especially likely and especially risky when marginalized people are at the center of the story.

This particular case exemplifies several challenges that have been plaguing journalism for years:

- Over-reliance on law enforcement as a source, which is flawed and non-neutral

- Lack of historical engagement with the community at hand

- The privileging of data over people’s experiences and observations

Journalists strive to include all voices and be as accurate as possible. So what went wrong? Because the community in that neighborhood couldn’t rely on the police for appropriate help, they didn’t call in enough for disappearances to register in the dispatch data.

Not only did the official data fail to show the reality of a dangerous offender on the loose – it actively obscured it. This gap between the official data and reality on the ground took a dangerous situation and made it even more dangerous for the people living it.

So, as journalists, what can we do? One of the first steps is to keep framing goals in mind throughout all of your reporting. Gina Kaufman, who cataloged the Kansas City example for Nieman Reports, listed several suggestions including avoiding relying solely on police for sources. The challenges listed above –and Patel’s framing questions – are another good place to start.

This bonus chapter will also cover hands-on tactics to get you started on ethical, forward-thinking journalism.

Avoid conflating groups

Many data sources come to a reporter aggregated, meaning it has been compiled or averaged from several sources or subcategories. Aggregated data isn’t inherently bad; sometimes it’s actually more useful than granular data.

But it can have the side effect of hiding, erasing or conflating variables. Just as we saw with the gap between data and reality in Kansas City, aggregation is something that carries more risk when covering marginalized groups.

For example, if you open up the US Census, you will most likely see data aggregated by state. You may want to drill down for more specific info, but it doesn’t necessarily carry ethical risks.

On the other hand, aggregation of people, like ethnicities, can have additional consequences outside of data analysis. Abigail Echo-Hawk, a Pawnee journalist, pointed out that grouping American Indians together with White people can affect those people’s rights, laws and resources, which are all influenced by the number of American Indians counted in the Census.

“How does that benefit the larger population, to have us hidden within the data?” Echo-Hawk said on Twitter. “It effectively whitewashes the data, turns Native people into White people.”

But what can you do if the data is presented to you already aggregated?

Francisco Vara-Orta, DBEI Director at Investigative Reporters & Editors (IRE), recommends asking the source for the most specific dataset possible. Once you’ve got it, provide your audience with context and be clear about the data’s limits.

Accurate data “allows you to cut through rhetoric that really harms people and leads to cyclical problems that investigative journalists want to solve,” he said. “You have to realize skill building doesn’t stop with learning Python or R.”

Diverse datasets

In addition to keeping DEI in mind during your regular reporting, diversity itself can be the driver of a story. Data from around the world can shine a light on race, gender and other faultlines as the key piece of information to investigate.

These are a few datasets that might be helpful for finding equity-related stories. You can find other datasets in Chapter 2, Searching the Deep Web, in the Data + Journalism textbook.

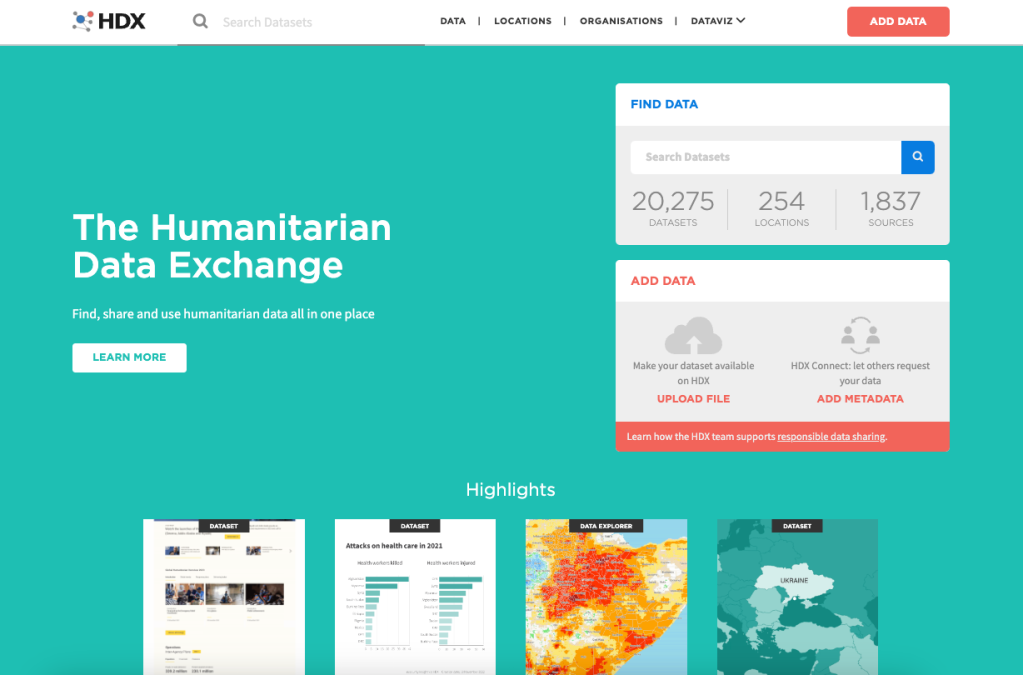

| Humanitarian Data Exchange | This is a hub of over 20,000 open-source datasets, mostly focusing on humanitarian topics like access to education, natural disasters and vaccine rates around the world. |

| US Department of Education Civil Rights Data | This enormous database of demographic info can be especially enlightening for newsworthy topics like school punishment, enrollment, and free and reduced lunch programs in US public schools. |

| Our World in Data Cancer Survival Rates | This is an example of a dataset from Our World in Data, an Oxford-run repository of data from around the world. The site allows you to overlay demographic info, like sex and race, to look for trends and make comparisons. |

| Pew Research Center Gender & LBGTQ Research Topic | The Pew Research Center is among the most trusted sources for opinion polling in the US. Here, you can find polls related to gender and sexuality, or navigate to other research topics like generation and politics. |

Use up-to-date language

One of the best ways to incorporate DEI in your reporting is to use accurate and sensitive language. Word choice can have extremely large impact, including offending readers, making some people feel unheard, or even causing complete misunderstandings.

In a 2022 IRE Conference session, speakers recommended using as specific language as possible to identify sources, even if it costs word space. There can be exceptions for headlines, they said, but even for broadcast and radio, it’s more important for your audience to understand the source than to save a few words.

For example, in the 2020s US, “Republican,” “Conservative” and “Trump supporter” might mean completely different things, or all be synonymous, depending on who you ask. The reporters suggested using specific terms like “a Conservative-leaing Trump supporter” instead. This goes for data sources as well.

You might be unfamiliar with specific terms if you aren’t a member of the community, so you can use style guides from authoritative sources like the communities themselves.

Popular style guides

Here area a few style guides – lists of appropriate terms and phrases – that are especially popular in the journalism community:

| Diversity Style Guide | The Diversity Style Guide is a compilation of other style guides from groups like the NLGJA and SPJ. It’s not entirely comprehensive but offers a great one-stop shop for many common questions you might encounter, like whether to use the word “sex” or “gender.” |

| Language, Please | The news outlet Vox published this guide for all journalists who aim to “thoughtfully cover evolving social, cultural, and identity-related topics.” It offers very detailed background and guidance on specific terms and is updated regularly. |

| Associated Press Stylebook | The heavyweight in the journalism industry has added timely instruction on sensitive topics like ethnicity, gender and political terms. It is mostly available as a paid resource but offers parts of the guide for free. |

| NABJ Style Guide | The National Association of Black Journalists (NABJ) maintains a style guide for issues pertaining to the Black diaspora (people of Black and African descent around the world). |

| NLGJA Stylebook | The Association of LGBTQ Journalists (NLGJA) provides a stylebook on terms related to sex, gender, sexuality and identity. |

| Reporting and Indigenous Terminology | The Native American Journalists Association (NAJA) offers succinct guidance on when and how to use terms like “Native,” “Indigenous” and “American Indian.” |

| Religion Stylebook | This guide from the Religion News Association (RNA) offers a large amount of expertise in a small amount of space – for instance, when to capitalize “Catholic” or what is celebrated during Diwali. |

Realistically, there is no need to try to memorize all of this guidance or read a stylebook from cover to cover. They are meant to be kept handy as a reference.

You can also sometimes find specific guidance for communities like First Nations people in Canada, conflict survivors in West Africa, or Uyghur speakers in China. It’s always better to be more accurate than more broad.

If you can’t find a guide that’s made by – or even for – journalists, you might find one from a government agency or advocacy group. For example, the New Zealand Ministry of Business offers guide to a words and icons in the Maori culture for trademarking purposes. If you’re using a non-journalism guide, you can assess the source for credibility and neutrality the same way you would any other (see Chapter 2 in Data + Journalism for more on vetting sources).

Capitalizing Ethnicities

Why is the ethnicity “Black” sometimes capitalized, while others, like “White,” are not? This is an example of how style can change over the years.

As of 2020, both the AP and NABJ encourage capitalization. A capital “Black” differentiates the word as an identifier of a group of people, rather than an adjective, like “a pair of black pants.”

The guides differ in that the NABJ capitalizes other ethnicities, like “White,” while the AP does not. (This chapter uses NABJ style.) The AP noted that White people tend to have fewer shared experiences, and there was less global consensus around the world for who is grouped together as “White.”

If you are unsure of a term, or if you want to understand the reasoning behind it, it’s probably best to consult the community in question. The SPJ Race and Gender Hotline would be a good resource for questions like this.

If you’re ever not sure of a word, spelling or identifier, it’s best to defer to the source themselves.

“When covering the LGBTQ community, we encourage you to use the language and terminology your subjects use,” the NLGJA wrote. “They are the best source for how they would like to be identified.”

Feature diverse sources

The diversity of a story’s human sources is another factor that has always been important, but is recently receiving more attention in the journalism industry.

In a basic sense, it’s important to have a diverse collection of sources in order to provide a balance of voices, experiences and perspectives in your story. It also helps your story avoid bias or one-sidedness. This is probably something you learned in your first journalism class.

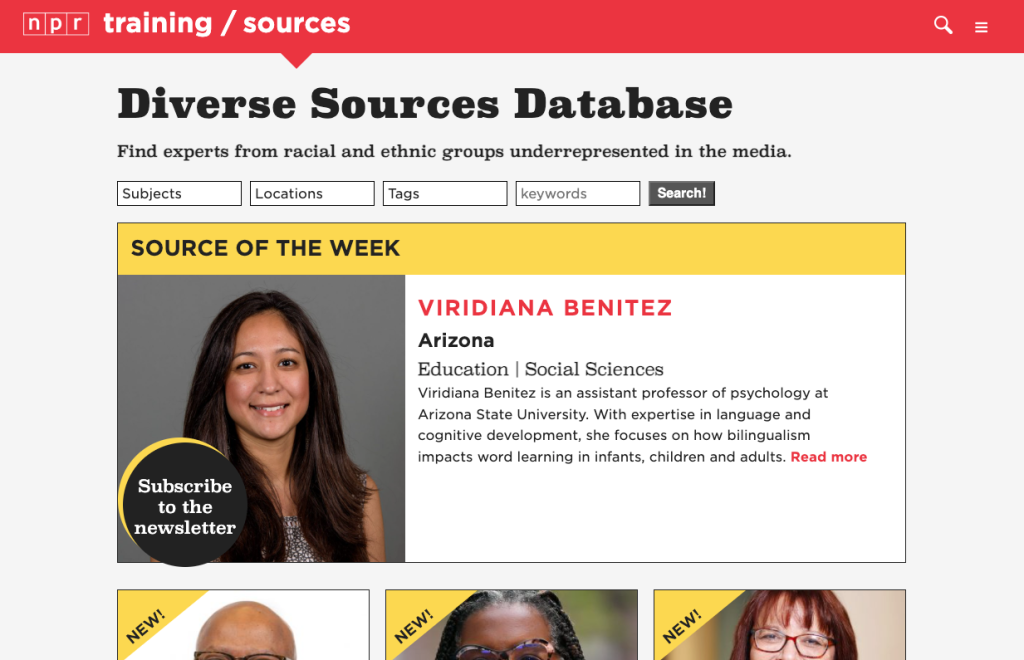

From a DEI perspective, it’s also important to include a diverse array of sources to overcome the existing disparity in sourcing. In 2018, National Public Radio (NPR) announced that an overwhelming majority of their sources were White and male, despite the outlet covering the entire US. Other outlets have published similar internal accountings.

Creating a more diverse body of work is something journalists have been working on for a long time, and every story helps. As Patel noted in her guide for Poynter, your story should utilize diverse sources regardless of whether diversity itself is the focus.

Diverse source databases

| NPR Diverse Source Database | NPR maintains a database of diverse sources on everything from sports to human rights. The site filters by state and topic, and even spotlights a source of the week. |

| Diverse Sources | This simply-named database lists nearly 1,000 experts across many science and academia-related fields. You can filter by expertise, language, time zone and other factors. |

| Editors of Color Diverse Databases | Editors of Color is a database of diverse media practitioners. It also offers a compilation of other databases, each with diverse experts in tech, politics, filmmaking and other industries. |

| Journalist’s Toolbox: Finding Diverse Expert Sources | This video shares several different resources for finding expert sources, as well as other tools from the Journalist’s Toolbox, a resource by SPJ. |

Source diversity audits

A specific technique for assessing story diversity is a tool called a “source diversity audit.” This is a survey or data collection you perform yourself, whereby you find out the diversity of the sources you are using or have quoted in the past.

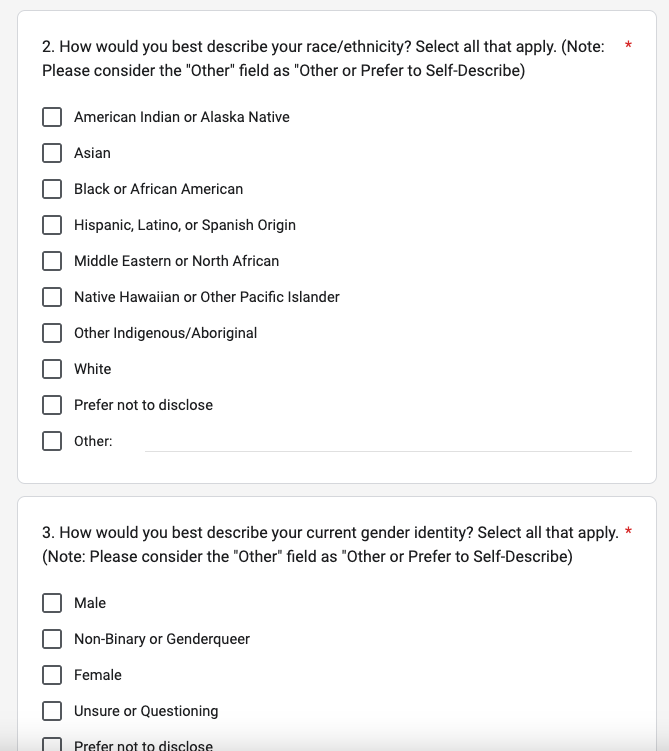

You can use a specific tool, like this one from Chalkbeat and the Reynolds Journalism Institute (RJI), or simply create a survey on your own. The Open Notebook wrote a guide on creating one of these surveys, and offers a template questionnaire you can use on Google Forms. RJI put together a well-researched list of terms to use for categories like race and ethnicity, in order to be as inclusive as possible.

Source Matters is another tool created by the American Press Institute (API). It offers automatic source detection and identification using natural language processing, and also includes expertise from the team of developers at API. Currently, Source Matters is available for a fee, and newsrooms can request to take part through its website.

Keep asking questions

This chapter has covered several challenges that may seem insurmountable to the average student or journalist. How can we enact these changes while producing daily stories and timely coverage? What can we do if sources don’t want to answer our diversity audit, or don’t have accurate data?

The answer is to be realistic about your goals and fall back to a central facet of journalism: Asking questions. For example, if a government agency doesn’t offer parsed-out data on its employees’ ethnicities, why not? Is the data collected? Is it private? Why or why not?

Vara-Orta suggested journalists ask these questions habitually, as a way of both soliciting interesting information and pushing for more equitable and accurate information for the public to use.

“That can sound activist, but really it’s just to serve everyone better,” he said. “Those are accountability questions, they’re not activism.”

Better data is better for reporters, which in turn benefits the public at large: the ultimate goal of journalism.

DEI Tools

Here are some tools you can use to assess your own work as well as plan for more inclusion in the future.

| SPJ Race and Gender Hotline | This tool from the Society of Professional Journalists (SPJ) offers experts on demand who can answer questions on sensitive topics. They are paid for their time by SPJ, to avoid placing the workload on other journalists of color. |

| Language, Please Inclusivity Reader Directory | An inclusivity reader is someone with knowledge of a sensitive topic at hand – like gender, ethnicity or history – who can proofread an article for sensitivity to marginalized groups. |

| Humaans | Visuals are another good way to include diversity and avoid stereotypes (see Chapter 10 for more on these topics in data visualization). If you don’t have something topical like a news photo or infographic, Humaans is a fun tool for creating royalty-free illustrations with a variety of skin tones, body types and backgrounds. |

| Proporti.onl | Proporti.onl is a small, independently developed tool that estimates the gender diversity of your Twitter feed. It is not comprehensive and shouldn’t be used for something official like a story – but it can be an interesting insight into the media you are ingesting. |